Masks off. Today I was speaking to Batida and Luaty, tomorrow lost extraterrestrials seared upon entry into Earth’s atmosphere. Meet Ikoqwe. An Angolan musical duo for whom the trite category of “genre-bending” is totally appropriate. One might even say otherworldly… The group is composed of Pedro Coquenão aka Batida, a kuduro producer known for musical bombs like “Bazuka”, and Luaty Beirão aka Ikonoklasta, an Angolan rapper with a history as a political martyr. I met the duo in the loud and buzzing press hall of Rennes’ Transmusicales, the 42nd edition of the renowned French music festival boasting a highly eclectic lineup where genres, disciplines and boundaries are just suggestions. Batida laid-back in a bright yellow Austin Powers-like chair, and Luaty sitting hunched over a stool looking both prim and proper. We say hello as I rip the mic out of my bag, commenting on Batida’s last conversation with PAM in Lisbon, his adopted home. The Lisbon interview (by our friend Kino Sousa) was a maze of topical politics and abstractions of the term “artist”. Adding Luaty to the fold for this go-around, I knew I had my hands full. The two have a lot to say.

Pedro was born in Huambo (500km south-east of the Angolan capital city), and has received a lot of attention for his approach to Luanda dance music culture. Production, choreography (with dancers Piny and André Cabral), percussion, crate digging, costume design; he seems to do it all. An armchair philosopher with a healthy dose of sarcasm that points to his ultimate humility, he’s a Chimera of an interviewee. Mysticism holds hands with irreverence in his work and speech. Luaty, on the other hand, is an emcee operating in the crosshairs of revolution. Sentenced to five-and-a-half years in prison (ultimately serving only a few months) for “planning a rebellion” against then President Jose Eduardo dos Santos along with 16 other activists in a kangaroo court, Luaty is oddly composed for a former prisoner of conscience. A soft spoken MC with a twinkle in his eye, there’s a kindness that doesn’t feel superficial, a hardened sense of compassion sprung through turmoil. Both have a top-notch sense of humor.

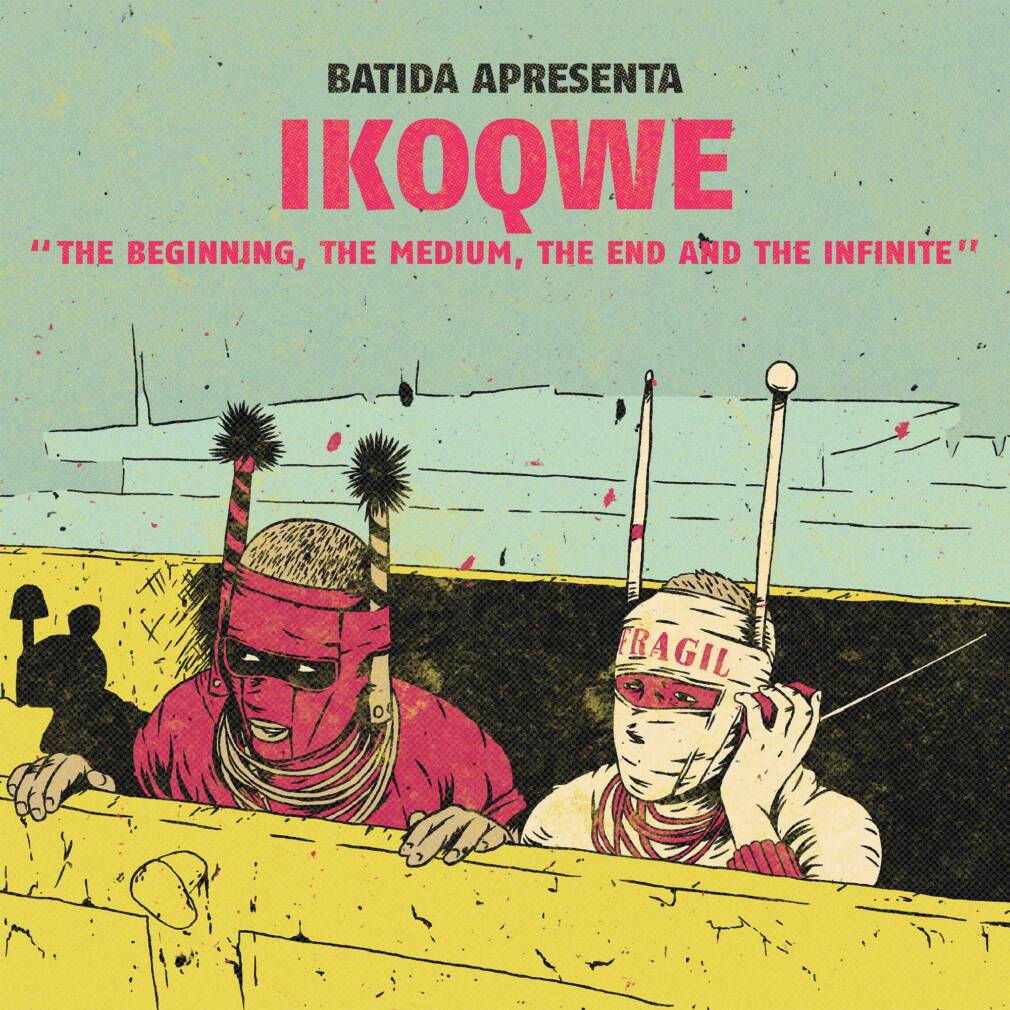

Matters of music, politics and cosmic revelation were discussed. Our one hour conversation has been heavily redacted for readability. The detours are plenty and the explosive creativity contained in their 2021 album, The Beginning, the Medium, the End and the Infinite, (“a super pretentious title” Pedro commented impishly) is ripe in their thought and speech. Join PAM in a look behind the curtain of the most exciting extraterrestrials (and humans) to swirl their fingers into the hip-hop of our blue planet.

I’ve understood Ikoqwe is a couple of masked aliens seared upon their entry into Earth’s atmosphere and suffering from amnesia. Where did this idea come from?

Pedro Coquenão (Batida) : It started off as myself not being able to step on stage, to give my image, or be a performer as I was before. So I needed somehow to find a way to defend myself. And if you have a mask it really gives you a distance from yourself to others. People are more focused on the mask than on yourself. I don’t want to be projecting my own face all the time.

Luaty Beirão (Ikonoklasta) : For me, when I was younger, coming into this music thing, I wanted to create a persona that was invisible. Characters such as Ghostface Killah and MF doom, I loved. I was absolutely infatuated with the concept. So once we had the characters I said, “Okay, maybe we should create a whole story around it and make that the identity of the duo.”

P : The mask thing is something that we have been doing as humans, since we’ve existed. It’s probably the same thing as making music or dance. The mask was always a tool to deal with demons. Hip hop just happens to be probably the best exercise we found over the last a hundred years or so on communicating with it because you can bring dance and painting and words and beats. Masks are more like on the pagan side of things, like to be more connected with your own demons and your demons are always changing

C : There’s some low hanging fruit with iconoclasm as well. Was masking up a way to avoid the pitfalls of mainstreaming?

P : You know, Luaty was killed. He was murdered as an iconoclast. That’s why I was like, yeah, you should join me because the people just killed you. You went from being an underground rapper respected within the community in Angola, and known in Portugal by a few MCs, to being a sticker, a Jesus Christ, Che Guevara type of guy.

*both laugh*

L : Yeah, we just don’t want to fit into the tiny space that mainstream demands you to be in. Especially in countries like Angola where there are very few groups that are created by the regime to entertain people. So you make a conscious decision. But if you become mainstream, you just accept it as a consequence of the path you chose. If being anti mainstream actually made you mainstream, you accept it.

P : You know Luaty was arrested for months? He went on hunger strike and I don’t know any rapper that has that on their bio. Check this guy out, he spent 36 days without eating. It’s something that would be really weird and stupid to do, but I’m sure that if we were on a mainstream level, that would be marketable. So yeah, we don’t use that at all. It was more like, oh my God, they destroyed your career as an iconoclast. You spent 36 days on the news when you should’ve been like an underground rapper or something. And you are on every newspaper cover! So you are not iconoclastic anymore. You’re an icon. What shall we do? There’s always these opportunities to transform things into marketable things, but here it’s more like using the masks, using the messages, using the thought provoking questions as the drive and then whatever comes later, it’s just consequences.

L : Once you take a different route, it’s very hard. You have to be promoted to have your song playing on the radio, to have a video, to have someone actually booking you, but they’ll be afraid of having people who speak against the government, you know? Once you accept that, you really embrace it as a form of living. This is a way we want to live and we accept that we will never make money out of this. We’ll never live off art, but we consider art so important to convey a message that we will do it regardless. So I think it’s a natural counter-culture that comes from the resistance of what you’re being fed… when you realize that it’s not uplifting you.

P : Although, I really want to be filthy rich. I want to make loads of money. *laughs*

C : Turning towards the music, there’s a lot of sounds in this project. A lot of local samples from Angola too right? How did you bring these in?

L : They’re a part of our growing up, coming up with traditional music, traditional instruments, like the kisanji – in some places they call it kalimba – or the dikanza..… our instruments make beautiful sounds. And when you blend them together and you add the modern sounding elements of electronic music, you create something unique. So even though we’re in our hip-hop or kuduro or whatever, you can see patterns and recognize the sound itself. Pedro is one of the guys that accepts that we should put forward elements that are beautiful and have not been used.

P : Yeah, going back to the idea, in this case of Ikoqwe, of early recordings in Angola of instruments that are no longer used, well some of them are, but they are not the most popular. If you go back to early kuduro and most of the pop music then in Angola, marimba started to be played on keyboards. And when you come out of a miserable scenario, eventually you think it’s way more cool to come up with a keyboard instead of coming up with something made out of wood, because it looks cheap or tribal or not sophisticated. You have a power that existed before countries were colonized, and we are both Angolans and we have a strong relationship with that country. It would be so much easier to go and go after a South African catalog or Nigerian catalog, or Congolese catalog because people are already into it. It’s already familiar.

But, again, it’s not so much about the consequences, it’s more about the cause, and the cause here is : let’s put these instruments into the light so these local producers can go back and sample that stuff. Or to create interest from outside of the country in our past. Eventually that can be validating for people that live in Angola to look at the instruments differently and think like, “okay, so maybe our dikanza is not just weird or unique. It’s unique and it’s GREAT. Or the hungo (single-string percussion instrument) yeah, it’s similar to the Brazilian berimbau but it started here!’

So why should we just let the berimbau talk? Why shouldn’t we just ask what the hungo has to say? It’s not about who started first. It’s more like what you have to say now. And that speech, the instrumental speech, the oral speech, the dance speech was deleted intentionally by colonialism.

The record (The Beginning, the Medium, the End and the Infinite) is all these attempts to connect lost memories, lost links, to bring back old stuff, to bring back masks, to bring back that Pagan power that is off of the radar of religion and colonialism. And bringing diversity because, in the end, all those instruments and all those recordings were in very different areas of the country. So the record doesn’t want to be genuine, or it doesn’t want to be like connecting the exact dots, but there was a certain preoccupation about wanting each sample to come from within that territory. Every sample that is on the record is used as magic, almost like a spell.

C : And then there’s hip-hop… How do the two come together and what does hip-hop mean to you?

L : At a very early age my cousins introduced me to hip-hop. It was back in 94, so Nas’ Illmatic was coming out, Snoop Doggy Dog’s Doggystyle came out the year before. It was spreading like wildfire. It really made you feel defiant, you know? Like, ‘This is wrong. Let’s fight it.’ That attitude immediately reflected on me. And also the context I was living in, in Angola, it immediately referred to it in the lyrics, about the concern I had and putting words together and communicating.

So yeah, hip hop is, I could say, a savior because it really shifted my attention to more important things where I couldn’t just be another happy go lucky guy that was born in the right family, the privileged. That would be inconsiderate of the underprivileged and the system that actually allowed me to be privileged.

There’s also Angolan groups that really started doing that in Portuguese. Listening to someone that is speaking about your country, your problems, your history in your language really moved me and made me aware that I’m an individual within a society. As soon as I become conscious of that, I also become responsible for taking part in something bigger than myself.

C : Politics and genres aside, the album is a lot of fun. There’s a part on “Bulubulu” where Luaty just starts laughing. How was it making the project together?

L : Sometimes you accept those accidents as part of the creative process and if it makes you laugh, I say, well, why should we take it away to make it look more serious? Just let it be. I really appreciate human beings and artists that have the courage to just be themselves and accept that they’re different from the rest. That incites me and sparks the creative side of me. And this is the kind of people I like working with.

P : What I like the most about working on this project is it allows us to express ourselves, to communicate with others between stupidity and very deep thoughts, worries that we have and things that are very heavy and serious. To be stupid once in a while also makes you more human…or alien, depending on the way you see it.

Listen to The Beginning, the Medium, the End and the Infinite.